On not being desperate

and why Look 45 of Vetements’ SS23 RTW collection is

As a rule, fashion media must border on hagiography. “All the history of fashion journalism is commercial,” largely due to its reliance on advertising dollars bequeathed to it by the brands upon which it reports. And so I was unsurprised that when its agents tasked themselves with assessing Look 45 of Vetements’ SS23 RTW collection—centering a shirt that read “STOP BEING RICH”—they largely declined to challenge this ordinance: Hypebae pronounced it an exemplar of Gvasalia’s “‘twisted imagination,’” Nylon volunteered it as a continuation of Vetements’ “typical ironic fashion,” and Highsnobiety deigned it, alongside several other graphic tees in the collection, “a total Friday mood.” Only W Magazine summoned the requisite bravery to suggest that “ironically enough, getting your hands on the shirt pretty much necessitates being rich.”

Paris Hilton one year ago refuted the image denizens of the Internet have been circulating for almost 20, featuring her in a wifebeater emblazoned with holy triumvirate “STOP BEING POOR” (all caps, perfectly justified, characters of each word vertically scaled vis-à-vis varying factors, as if alluding to the various ever-clashing sociocultural, political, and economic stakeholders that would be obliged to align in order to Make Poverty Stop Happening)—a dictatorial block of a directive that, emerging from the mouth of perhaps anyone else would be cause for at least temporary cancellation but here, donned by Paris, a veritable girl next door (her roots are visible in the photo) if not for her eternal reign in the Y2K Hall of Fame, becomes something beautiful, even seraphic: her figure almost perfectly occupies the center of the composition, drenched in the fickle glow beaming down from the halo of the limelight far above. Her arms are thrown up into the air, as if to glamorously emphasize the lack of agency she, or any of us really, have over the world we live in—a world that makes this painfully good advice—as if to say guys lol i’m just the messenger so like, please don’t shoot me, ok? that rly wouldnt b hot…

It’s unclear who took the photo, and until they came forth, we had no idea who had, by altering it, had mutated the real into simulacrum. The wifebeater Paris actually wore was printed with the even holier triumvirate “STOP BEING DESPERATE”—the revisionism is but farce, false memory implanted by an artist into our collective online unconscious. Yet, as false memories tend to do, this one catalyzed a contingent reality in the look under examination.

Look 45 manipulates a line that was never scripted in an episode of history that never aired (I don’t watch TV). Look 45 explains the joke (nobody worth telling needs the clarification). Look 45 is the catch-22 of self-congratulatory bourgeois posturing (as W Magazine indicated, buying the t-shirt will definitely set you back at least several hundred dollars—meaning you’re probably doing exactly what it tells you to stop doing (being rich)). Look 45 is evidence (beyond a reasonable doubt, creeping into the gulf of incontrovertibility) that “spectacle is the sun that never sets over the empire of modern passivity” (to quote Guy Debord, philosopher behind The Society of the Spectacle). Look 45 is a case study in “how to incorporate memes into your marketing strategy” (Guram, who is now Vetements’ creative director, used to manage its business dimension before Demna retired to Balenciaga, and Demna himself admits in an interview with SSENSE that “Vetements is a business…We are not a conceptual or artistic project. We are 100 percent product-oriented and open about it.”) Look 45 warps innocuous bit into philistine glut. Look 45 is the death of cipher. Look 45 is desperate. Paris Hilton warned us not to be.

Look 45 operates at the intersection of fairytale (the simulacrum that is Paris Hilton telling us to STOP BEING POOR) and financial stability (the status of being RICH that is required to acquire it), coincidentally-poetically the message of a previous tee by Vetements:

The Fashion Law suggests that “there is certainly merit to the awareness-raising properties of t-shirts…and Twitter, and our ability to us[e] our bodies – and our social media accounts – as walking billboards for our causes…[but] this is is different than actually acting upon the ideas that we present [therein].” Yet in Look 45, the only call to action is BUY NOW, and to say there is merit to what is essentially virtue-signaling feels generous, especially when it comes to a tee hawked by a luxury brand.

When it comes to selling a moral ideology, the philosophy espoused by the American Association of Advertising Agencies can be applied:

Despite what some people (corporations) think, advertising can’t make you buy something you don’t need. If you happen to be, you don’t need to stop being rich. In fact, if you want this t-shirt, it’s essential that you continue being that way.

T-shirt activism deactivates. T-shirt activism renders its practitioner a suspicious character. T-shirt activism is only euphemism because it transmutes into narcotizing dysfunction, a sociological concept theorizing that the more the media deluges the masses with a particular issue, the more apathetic they become to it. Wearing a T-shirt makes a statement. And making a statement becomes a substitutable good for realizing the greater good. It’s ironic that the model cast for Look 45 Freudian-stumbles on the runway, as if herself narcotized, unable to bear the weight of the lie clinging to her body-as-billboard:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

The parody that is Look 45 opts against reusing the medium of the wifebeater. The shirt appears to be sleeveless, yet cannot be formally classified as “wifebeater” due to its high neckline, which hides the clavicle. A true wifebeater bears a deeper neckline.

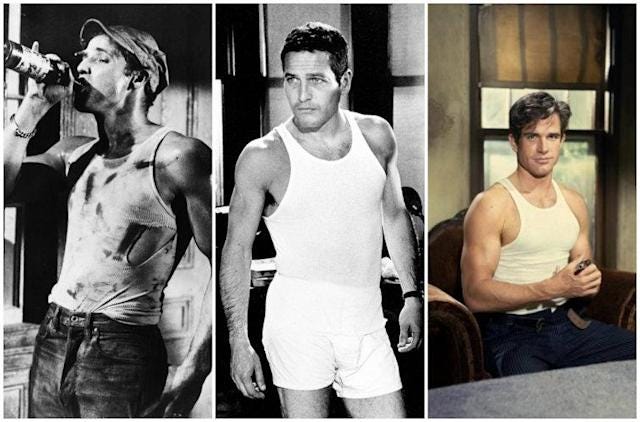

Contributing to the delicate irony of STOP BEING RICH is the medium of the message: a wifebeater. The term “wifebeater” became associated with the undershirt around 1947, traditionally connected to “lower class, brutish men,” in part due to the work of Hollywood at the time:

The shirt bore slang names such as “guinea tee” or “dago tee,” relying upon ethnic slurs to designate the shirt “something poor, dirty “‘others’” wore.” STOP BEING POOR emblazoned upon a garment with such a history is true irony, chastising an entire class of a people while appropriating their wardrobe. So had it tapped into this cognitive dissonance by embracing rather than eschewing the wifebeater, Vetements might have done a better job performing its activism in Look 45.

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu theorizes that “a work of art has meaning and interest only for someone who possesses the cultural competence, that is, the code, into which it is encoded.” I extend his theory to fashion: a certain amount of cultural capital is required to discern the relevance of Look 45 to the discourse (side note: historian Christopher Lasch famously warned against relevance, observing the ways it masks that which is inherently “intellectually undemanding.”) You need to attain a certain quota of cultural capital—earned specifically online—to “get” Look 45. Interestingly enough, Vetements’ AW20 collection included a tee that politely underscored its aversion to social platforms:

Vetements’ quiet philosophical pivot feels hypocritical, as Look 45 evidently contradicts this ethos: Look 45 never could have existed in a world sans social media. In politics, when a candidate “flip-flops,” it can be interpreted to suggest a certain level of “calculation.” Fashion is politics, and politics is always in fashion. Perhaps Vetements is betting on our collective digital amnesia—forced to bear witness to image post-image post-image every day into eternity-or-the-end-of-the-world, we are unlikely to immediately recall their earlier work. And they are unequivocally betting on the reference’s Y2K virality to move the product upon which it finds itself appended. “We’re in a church of the future, where you belong simply by being your true self,” Guram opined less than a month prior. To be authentic, you must possess a coherent value system. Does Vetements know who they are? I’m betting on excommunication.

It’s striking that the tee is styled with an iteration of a particular cakebox-pink tulle robe that has made headlines (I Vogue: Does This Robe Make You Think of Death?, II. Reductress: 4 Long Robes to Murder Your Husband In, III. People: This 'Very Glamorous' Amazon Robe Is Going Viral on TikTok for One Pretty Amusing Reason):

The interplay of the robe and the tee spawns a disconcerting cognitive dissonance within me. The alleged presentation of a discrete symbolism of the people oscillates: if the tee’s message is to “STOP BEING RICH,” then why would a model LARPing as an ostensibly wealthy widow don it?

Is Look 45 deliberately ironic? Is it a rigorous artistic work of “calculated” conceptualism, devised to conjure the image of a widow who ends her rich husband to send a message, S.C.U.M. style: “STOP BEING RICH”? Are you casting off this diatribe as yet another one of my neurotic bouts of pseudo-intellectual contrarianism?

I want to walk in the shoes of this murderess-turned-widow. I yearn to unravel the rhizome of her psyche. But her jeans are far too long, dragging on the floor, hiding what lies therein. She might not even be wearing shoes.

I want to look into her windows (eyes) to catch a glimpse of her soul but she has the blinds turned all the way up (is wearing dark sunglasses).

Investigative voyeurism has failed me, so I reluctantly default to conjecture. I think that if I were smart enough to figure out how to kill my rich husband and get away with it, I wouldn’t have been dumb enough to marry him in the first place. I wouldn’t welcome a homicide detective into my home wearing something so incriminating. And I definitely wouldn’t be dumb enough to think that killing him would Make Wealth Stop Happening, or even that the deed could be repurposed as a rallying cry for a populist movement—after all, I wouldn’t be able to tell anyone what happened lest the story find its way back to the police. Unless I was willing to spend the rest of my life in jail in the name of “Justice.” But if I were such an ascetic, willing to forfeit the frills of life, I probably wouldn’t be wearing such a frilly robe to begin with. So I am ruling out Look 45 as (good) performance art.

In his show notes, Guram describes his love for Malibu Barbie, one of the motifs of the collection. How he bought his cousin’s using “all the savings [he] had from [his] birthdays, and Christmases.” How “at night when everyone would sleep, [he] would take her out of a hidden place, and make dresses for her.”

Malibu Barbie debuted in 1971. According to Barbie’s official site, barbiemedia.com, Malibu Barbie was the first Barbie to have her eyes face forward, “thanks to the groundswell of the feminist movement and female empowerment” (previously, Barbie had “a secretive side-eye, suggesting [she] knew a fun secret”). Similarly, the model in Look 45 faces forward, looking seemingly directly into the camera—she’s on the clock, after all. Yet Paris, in the image of her in her digitally altered tank, looks away from us, making the performance all the more authentic—she doesn’t know that we’re watching, and it’s not even really a performance, because the event never happened—and for the longest time, we didn’t know who doctored the image to make it look the part. The anonymity of its author, and their lack of a discernible agenda—as opposed to the global brand behind its appropriation, and their “product-driven” underpinning—further reinforces the honesty of the former while rendering suspect that of the latter.

Paris Hilton long ago acknowledged her association with Barbie:

Of Barbie, Paris once said: “She might not do anything, but she looks good doing it,” a quality she happens to share with T-shirt activists (I do want to underscore that looking “good” is subjective, and while Barbie is objectively hot, the T-shirts these “activists” sport are not).

"Paris Hilton the character is not the real me," Paris told PEOPLE in 2020. "It was an outer shell. How the world perceives me and who I really am is so different." Paris speaks of a "Barbie persona" she “manufactured” in order to sublimate the trauma she endured from abusive experiences at boarding school. The real Paris is to her “barbie persona” what activism is to the practitioners of its bastardization. Except the relationships between the variables are inverted: “Paris Hilton the character” was developed reactively, post-trauma, but activism is playacted by the T-shirt activists preventively, to avoid a faux pas they perhaps might inflate into (pseudo-)trauma: the fear of being labeled “bad,” of appearing aligned with a morally reprehensible minority, out of touch with the latest trends in social justice. It doesn’t occur to them that, if you’re doing nothing, maybe you shouldn’t say anything.

In his show notes, Guram also explains his decision to hold the runway show at Tati, a cherished French clothing chain that closed down after 70 years:

"Creativity comes from the lack of the means. As we couldn’t afford nor find any fabrics during the war time, I would take these cheap bags, cut them and make designs out of them. My first design patterns came in these blue, red and black check. Later on I realized what I was making my first garments from, was a knock-off version of the iconic Tati bag. So when I was told Tati went out of business, and will be demolished, I knew my first show had to be there."The slogan Tati’s founder chose to embody his brand? “Tati, les plus bas prix” (Tati, the lowest prices). One shopper nostalgically vouches for its sincerity, describing the retailer as somewhere “you could always find something you could afford, no matter how little money you had.”

Tati walked the walk before Look 45 could talk the talk. The retailer actualized the ethos to which Look 45 desperately attempts, but ultimately fails, to lay claim. Holding the show on such sanctified ground is anachronistic, adding insult to injury. And it acts as agonizing testament to the larger cultural trend that seeps through the postmodern arc of history which we inhabit, one that Christopher Lasch describes as “a politics of theater, of dramatic gestures, of style without substance.”

Image gaslights reality. Fiction tyrannizes truth. And only facade remains, but it is all too easy to demolish, as no foundation lies beneath it. Quite the eccentric architectural decision.

Revisiting the collection, I realize that Look 45 is implicated by Look 18, in that it features a T-shirt with a message that acts as the manifesto that led to Look 45:

It seems that the day Vetements conceived Look 45, they really weren’t planning on doing shit.

Mission accomplished.

Hi! 😊 Don't know if you might be interested but I love to write about sustainability (fashion, travel and our relationship with clothes). I'm a thrift shopping and vintage clothing lover who likes to explore the impact textile industry and consumistic culture have on the environment and also what people can do to shift the tendency.

• • •

https://from2tothrift.substack.com/

⛈